A “how to” guide for injury prevention at a team level

Injury prevention in sports is important. Injury results in real economic costs (hospitalization, doctors appointments, physiotherapy), as well as time off from work/school for participants hurt while playing sport. The implications for teams are also important, having players unavailable due to injury negatively impacts team performance(1). No one wins when players are injured.

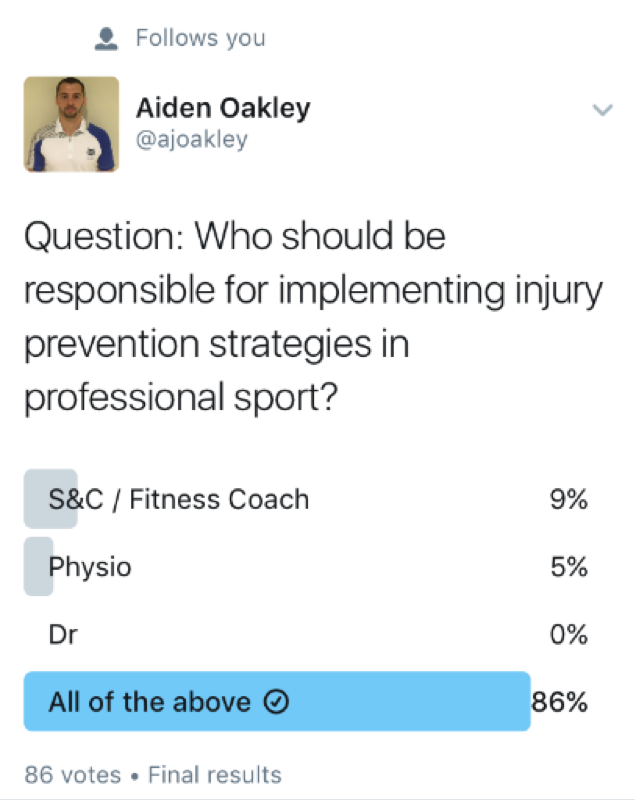

So how do we manage the problem? Firstly, we need to establish who is responsible for injury prevention. Is it the coach, S&C coach, physiotherapist, biokineticist/physical trainer, team doctor or sport scientist? This tweeted survey from 2016 (figure 1) put the same question out to the twitter community, and established a small consensus – its everyone’s problem!

Recent research in sports science reinforces this sentiment. One of the most important injury risk factors in sport is the training load that participants are exposed to(2). Since coaches are responsible for prescribing training, this makes them key contributors to any teams injury outcomes. The responsibility for injury prevention cannot simply be conferred to the medical or conditioning staff, when they are not in control of most of the factors that influence injury. Instead, an understanding needs to emerge that athlete health and athlete success are closely linked, and that all staff within a system are equally responsible for these areas(3). My recent research paper illustrates how effective this type of thinking can be(4)!

Now that we have both coaches and medical staff on board as contributors to the injury prevention program, the logical next question is where do we start?

1. Quantify the injury problem and understand the context

The logical first step in any injury prevention effort is to determine whether there is an injury problem that needs to be addressed. This requires “injury surveillance”, which means that teams need to at the very least keep track of the number of injuries players sustain, and the duration of time that players are injured for (injury severity). Additional useful information that can be collected includes that type and location of injury, as well as the mechanism and circumstances surrounding injuries.

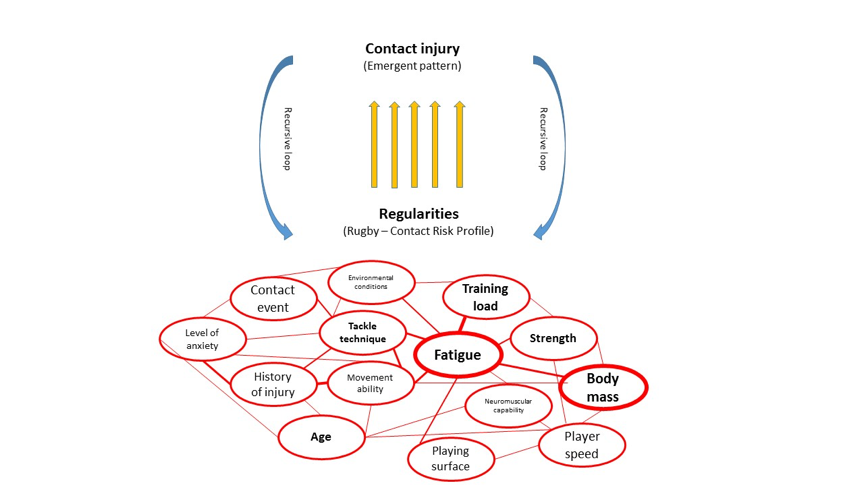

This sounds like a lot of work, and it is, but the alternative is not good. You see if you don’t have data, you’re guessing. One of the most important recent advances in the field of sports injuries is an understanding that injury patterns are context and organization specific. You see, no two teams are identical. Each has its own variations in playing personal, game style and training preferences. The combination of all of these different factors creates a “complex system” that will result injury outcomes that are particular to that system(5) (figure 2). In simple terms, the injuries that a team experiences are a result of the ‘system’ that the team has created.

This is important because teams need to address the injuries that result from their ‘system’. Here is an example: Hamstrings strains are among the most common injuries in football(6), and Nordic Hamstring curls are an especially effective exercise for reducing hamstring injury incidence(7). So should all football teams implement Nordics as part of their training regime? The answer to this question depends on whether your team regularly suffers hamstring injuries. If so, this may be a good intervention. If not, introducing an additional exercise may upset the delicate balance of the system that has been established. Perhaps your team doesn’t suffer many hamstring injuries because you complete a high volume of high-speed running in training because of the counter attacking style that the coach employs? In this context, adding Nordics to the program could result in unnecessary fatigue that increases the number of injuries that occur. In other words it is important that the injury prevention program is driven by the needs of the team.

2. Determine which injuries carry the biggest risk?

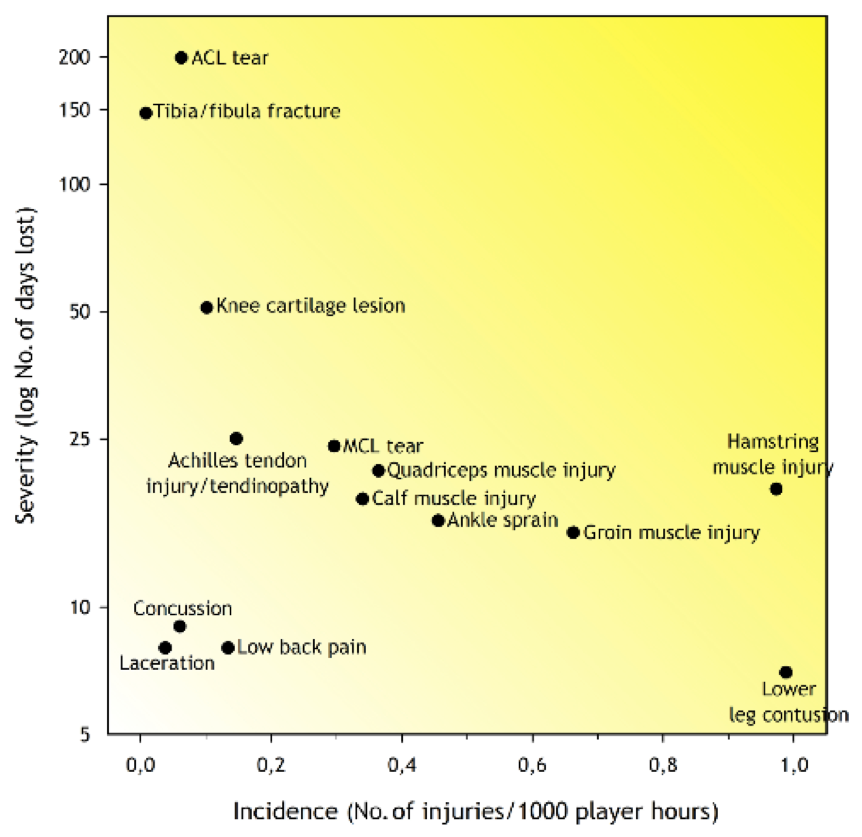

To establish the areas where teams might get the most “bang for their buck” in injury prevention, it is useful to work out what injuries result in the greatest burden (total time lost) to the team(8). Some injuries occur relatively infrequently, but result in a large amount of time-loss (e.g. broken bones). Other injuries may resolve quite quickly (e.g. contusions), but may also occur frequently. Injury burden can be calculated by multiplying the injury frequency (how often injuries occur) by the mean injury severity (how long injuries take to resolve)(8). The injury burden figure shows which injury types result in the most time lost to injury. Figure 3 illustrates the relationship between the severity and frequency of the 14 most commonly reported injury types in a football team. The darker the yellow shading in the graph, the greater the ‘burden’ that type of injury represents. In this example, the greatest burden comes from ACL tears and hamstring strains and so this is where the team should focus their injury prevention efforts.

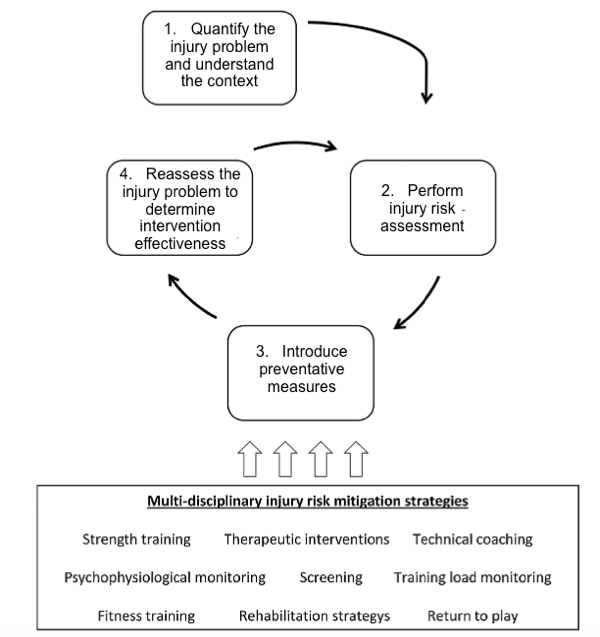

3. Introduce preventative measures

Once the best targets for injury intervention have been established, consideration needs to be given to the best ways to address these problems. At this stage information from injury prevention research on interventions that have been successful previously may be useful, but practitioners should always consider how this research may apply to their context. In addition, many potential injury interventions have not yet been empirically assessed by formal research, and practitioners will need to rely on their experience and expertise to make the best possible decisions.

An approach to this process that has been shown to be successful in the past(4) is for all members of the coaching and medical team to suggest interventions from their area of expertise. Coaches may suggest modifications to technique, while physiotherapists might recommend the inclusion of a particular exercise or stretch in the program. Interventions should then be assessed based on their feasibility within the program. For example, teams with limited financial resources can’t monitor high speed running loads through GPS, even if this is ‘best practice’. Further, a team with limited training time may not want to extend their warm up, and may address a problem through educating players to perform certain exercises in the own time. Interventions with the potential to make the greatest impact with the least disruption to the teams established ‘system’ should be prioritized.

4. Assess the effectiveness of the interventions

Once the coaching and medical teams have decided on the interventions they’d like to implement, all that is left is to execute the plan, and assess the results. The assessment of the results occurs via continued injury surveillance through subsequent seasons. At the end of each season the coaching and medical teams should assess the effectiveness of the interventions they have made in terms of reducing the overall injury burden, and burden of injuries targeted for intervention. Ineffective interventions should be discarded, and effective ones retained. It should be acknowledged at the outset that all intervention have the potential to have unforeseen consequences (through disruption of the dynamic system), which is why the effectiveness of interventions needs to be continuously reassessed. It should also be recognized that the system will evolve over time. Players get older and their training increases, team tactics change over time. Therefore continuous assessment of the injury burden and context is required for teams to be able to be responsive to changing demands and emerging injury problems. Injury prevention should be seen as a process that takes place through multiple cycles, rather than a once off intervention (Figure 4).

References

- Williams, S., Trewartha, G., Kemp, S.P., Brooks, J.H., Fuller, C.W., Taylor, A.E., Cross, M.J. and Stokes, K.A., 2016. Time loss injuries compromise team success in Elite Rugby Union: a 7-year prospective study. Br J Sports Med, 50(11), pp.651-656.

- Gabbett, T.J., 2016. The training-injury prevention paradox: should athletes be training smarter and harder?. Br J Sports Med, pp.bjsports-2015.

- Mooney, M., Charlton, P.C., Soltanzadeh, S. and Drew, M.K., 2017. Who ‘owns’ the injury or illness? Who ‘owns’ performance? Applying systems thinking to integrate health and performance in elite sport.

- Tee, J.C., Bekker, S., Collins, R., Klingbiel, J., van Rooyen, I., van Wyk, D., Till, K. and Jones, B., 2018. The efficacy of an iterative “sequence of prevention” approach to injury prevention by a multidisciplinary team in professional rugby union. Journal of science and medicine in sport.

- Bittencourt, N.F.N., Meeuwisse, W.H., Mendonça, L.D., Nettel-Aguirre, A., Ocarino, J.M. and Fonseca, S.T., 2016. Complex systems approach for sports injuries: moving from risk factor identification to injury pattern recognition—narrative review and new concept. Br J Sports Med, pp.bjsports-2015.

- Arnason, A., Andersen, T.E., Holme, I., Engebretsen, L. and Bahr, R., 2008. Prevention of hamstring strains in elite soccer: an intervention study. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports, 18(1), pp.40-48.

- Petersen, J., Thorborg, K., Nielsen, M.B., Budtz-Jørgensen, E. and Hölmich, P., 2011. Preventive effect of eccentric training on acute hamstring injuries in men’s soccer: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. The American journal of sports medicine, 39(11), pp.2296-2303.

- Bahr, R., Clarsen, B. and Ekstrand, J., 2018. Why we should focus on the burden of injuries and illnesses, not just their incidence.