Interval training sessions derived from maximal aerobic speed

Getting the most out of your pre-season testing and training

Its February, and all around the country, that means that teams are putting in the hard yards in preparation for the winter sports season that is rapidly approaching. The theme of this post therefore, is hopefully to provide some assistance in getting your team fit in the most efficient way possible. This is more of a strength and conditioning post than a strict sports science offering, but I think its important for both groups share a fair amount of cross over in this area.

The first thing most coaches want to do at the beginning of a pre-season period is “testing”. While its not the main thrust of this post, I’d like to make a short commentary on the process of testing, what we should test and why we should test it.

The first priority of testing in most practical contexts should be efficiency. Aside from some very well organized sports that mandate lengthy pre-season preparation periods (NFL, AFL), you can be sure that the vast majority of practitioners are working against the clock to get their players prepared. The question therefore is whether the information gained from a testing session is more valuable than the gains that could be achieved from a dedicated training session. The answer to this question depends on what you are going to do with the information. In my 10 years in this industry, I have never heard the following statement –

“Looks like our boys are strong enough now, lets stop squatting for a month.”

Coaches have the same attitude towards speed work. It is inevitable that strength and speed work will form a major part of any good training program, whether or not the athletes in question are well developed in these areas. This being the case, I would argue that a dedicate 1 rep max testing session might be a waste of valuable training time, when similar information can be gained simply by monitoring the weights pushed and times run during regular training sessions. You don’t need dedicated testing to determine if your athletes are getting stronger or faster.

So what should we test? My principle is that I only test things that are going to affect my athletes programming. Aerobic energy system development is a vital part of any pre-season training program. In team sport setting these are regularly assessed using the beep or yo-yo test, both of which are complicated by the need for sound equipment. (Strangely, no one designs training grounds with plug points that are easily accessible).

While both these tests certainly discriminate which players have the better aerobic capacity, it is rather complicated to determine specific training speeds and distances for players based on the results of these tests. As a result, I regularly see groups of players, with vastly different running abilities doing the same training session. The guys in the front being under stimulated, wondering what all the fuss is about, while at the same time the guys at the back are having near-death experiences.

We should be chasing individualization and specificity in our training at all times, to try and ensure that each athlete a session matched to his individual ability at every practice. This is why I like MAS testing and training.

Very simply, you should choose a distance that will require a maximal aerobic effort to complete, and get your athletes to run this as fast as possible. The physiology textbooks tell us that we need at least 3 minutes of hard activity to reach maximal cardiac output, so for most mortals a 1000m run will do. Personally, I like 1600m, but you should choose an appropriate distance based on the relative running profile of your sport. You can run the distance as shuttles on a 100m sports field, which makes the test convenient and easy to administer. Simply record the time that it takes each athlete to complete the distance.

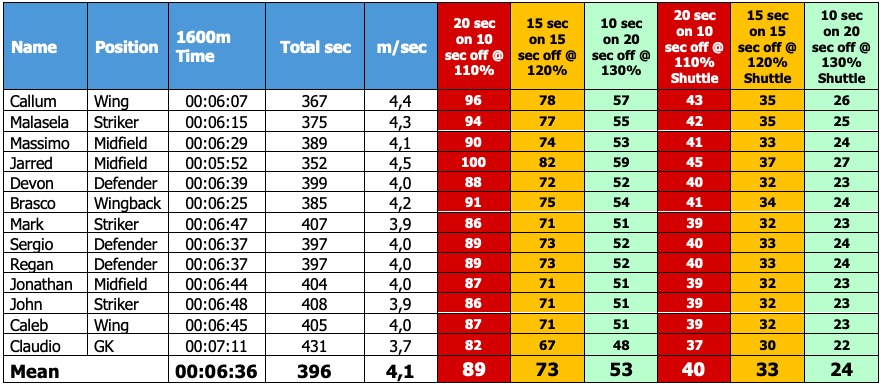

Now its spreadsheet time! Enter each athlete’s performance into you spreadsheet, and use this to calculate his or her average speed in (m/sec) for the MAS test (Figure 1). You can now use this value to calculate the distance that they should cover in a specified time. In the example below, I have calculated the distance for 20 sec, 15 sec and 10 sec intervals at 110%, 120% and 130% of MAS. Another clever little trick, if you have limited space, or just want to add in additional turns and accelerations is to calculate the running distance done as a shuttle run. I reduce the total distance by 10% for shuttles to account for the stop, turn and acceleration required.

This system allows for individualized training to be quickly and easily planned for a large group of players, with a range of running abilities. Obviously, the art of coaching is still for the coach to select the reps and intensities that would elicit the greatest physiological adaptation. Given the time, I would certainly recommend making players spend significant amounts at sub-maximal intensities (e.g. 6 x 4mins @ 80% MAS) to elicit central cardiac adaptations. However, since most of us don’t have that amount of time available, high-intensity intervals (e.g. 4 sets of 8 x 20 sec @ 110% MAS) are effective at producing improvements in aerobic capacity in a relatively short training period!