Coaching female athletes Part 2 – Put the athlete first!

As described in my previous post, I have recently moved into a role where for the first time I am providing S&C coaching to a group of high-performance female athletes. Part 1 of this article was a collection of information on the differences between male and female athletes, that I had gathered to inform my practice in this role. This post is a reflection on how I have modified my practice both in response to the research I’ve done and as a result of lessons I’ve learnt through coaching this group.

I’d like to start out by stating that female athletes are no less able, or less competitive than their male counterparts. In fact, the group that I’m currently supporting regularly impresses me with their work ethic and hunger for success. They are all exceptionally busy people who balance careers, studies, relationships, motherhood among other things, and still turn up like clockwork motivated and enthusiastic for every session. They work exceptionally hard in training, and I can honestly say there is no difference in effort levels from similar male groups I’ve coached.

Despite this, I’m about to make a case for how and why I do things slightly differently for the females I work with. I’d like this to be recognized as my attempt to tailor my coaching to better suit my athlete’s needs, not an attempt to perpetuate any of the stereotypes related to women being less able, or less competitive athletes. I treat these women as athletes first, setting high expectations and standards of performance, but modulate my coaching behaviour to make the coaching relationship as effective as possible. My second disclaimer is an acknowledgement that needs vary by individual, and that while I generalize about female athletes throughout this post, I aim to treat each athlete as an individual. Once I know an athlete well, I stop using my ‘rules of thumb’ regarding what is better for males or females, and start using my experience of what behaviours they react best to.

The first thing that became crystal clear to me is that female athletes appreciate social connections much more than their male counterparts. The team is more than a collection of players and coaches, and is in effect a social circle to which they dedicate a significant amount of time. As such, there is a spirit of cooperation and empathy among players that I don’t always see in male teams. In this context, the old adage “They don’t care what you know until they know that you care” is particularly true. Female athletes don’t need their coach (or other players) to be their friend, but they do appreciate coaches (and other players) getting to know them, their personality and what motivates them. This demonstrates that you value them as people, not just players.

With this greater social need in mind, I’ve deliberately adopted two behaviours to try and address this for my players. Firstly, wherever possible I try to arrive early for practice, and to linger for a few minutes once training is over. This provides opportunity for incidental conversations where I can get to know players a little better than I would if our only interaction was while coaching. Secondly, when considering motivation tools, I focus on group goal setting rather than inter-individual competition. This collaborative approach leverages the social capital within the group to drive performance.

A second important consideration for me is that female athletes have a more ‘whole-brained’ way of thinking11, meaning that they are more concerned with the “bigger picture” and relationships between things than male athletes are. The net result of this is that female athletes ask “Why?” a lot more often than males. In the beginning, I was regularly asked “Why am I in this group, not in that group?” or “Why are we doing these exercises, and not those?”. This has been quite refreshing for me! As a rule, I try to encourage athletes to understand why they are doing what they are doing in an effort to make them more independent, and so I welcome questions. On the other hand, the number of questions I was getting made me conscious that I wasn’t explaining things as well as I thought I was. I’ve made a conscious effort to provide the reasons for programming decision I’ve made since then, and I’m now not getting the “Why?” question as frequently!

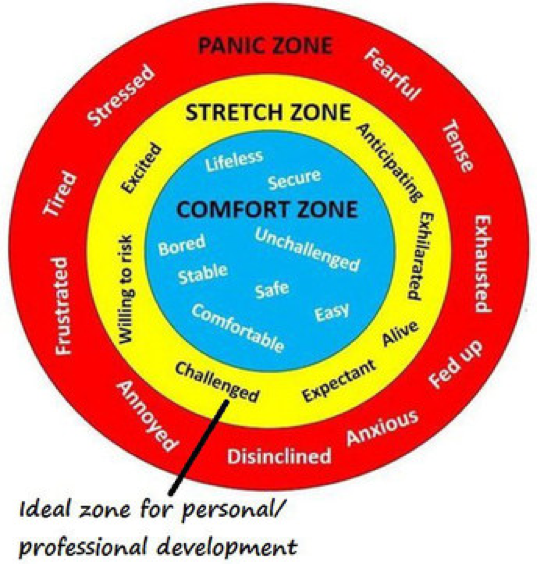

A final important consideration for me is that female athletes have a desire to be more collaborative in determining their training program than the male athletes I’ve worked with. Often males are quite happy to be told what to do, as it saves them thinking about it. In contrast, female athletes have quite a clear concept of their own strengths and weaknesses. They want a program that accommodates these, and don’t like the cookie-cutter one size fits all approach. I learnt quickly that asking the girls to do something too far out of their comfort zone either lead to disengagement, or reduced intensity of effort while they were finding their feet again. I rationalized this using the comfort-stretch-panic model (Figure 1).

Because there is a wide range of training experience in my group, I struggled to regularly pitch my sessions at a level that kept everyone in the desirable “stretch zone” all the time. One strategy I have used is to occasionally modify training on the basis of the girls’ feedback, but this requires one on one discussions that aren’t always possible in a team setting. What I have found very effective is simply to provide a number of choices within the training session. By providing a range of exercises suited to athletes of different experience and proficiency levels, I can allow athletes self-select what they feel is most appropriate for them. This has massively improved engagement and our training outputs!

As I sit here reading this back, trying to plan my conclusion, I realize that many of the coaching behaviours I’ve described are just good coaching behaviours. • Care for your players. • Get to know them. • Provide reasons for training decisions. • Collaborate in planning the training program. • Pitch training at the appropriate level. This is not coaching rocket science, nor would any of these behaviours be inappropriate in an all male setting. One of the central tenants of coaching is that we need to align our coaching with the needs of the individual2. Its simply good practice to be continually asking ourselves what these needs are, and what we can do to meet these more effectively.

References

- Brizendine, L., 2006. The female brain. Broadway Books

- Abraham, A., Saiz, S. L. J., Mckeown, S., Morgan, G., Muir, B., North, J., & Till, K. (2014). Planning your coaching: A focus on youth participant development. In C. Nash (Ed.), Practical Sport Coaching (pp. 16– 53). Abingdon: Routledge.