Coaching female athletes – What’s really different?

It has been a momentous last few months in female sport, with a number of significant milestones achieved. Firstly, the recent Rugby League World Cup hosted by Australia was the first to ensure equal provision for the male and female competitors. This meant that for the first time ever men and women were treated to the same standard of facilities, accommodation and medical support at an international tournament. On top of this both the men’s and women’s finals were played on the same day, in the same stadium affording equal status and recognition to both teams(1). Hot on the heels of this triumph, Australia announced that its Women’s Rugby Sevens team would be paid the same as the Men’s team(2). Here in the UK, the RFL has recently rolled out the Women’s Super League, the first national women’s rugby league competition. It might take a while for the rest of the world to catch up with the forward thinking Australians, but one thing is certain, women’s sport is experiencing a period of unprecedented growth!

Personally, I have recently taken on two different roles that require me to coach, and support the development of female athletes. I’m a little embarrassed by the fact that I’m now in my seventeenth year as a coach, and this is the first time that I’ve had any level of extended exposure to coaching females. Despite being relatively experienced, I’ve found myself questioning a number of my usual approaches. I’m constantly wondering whether I am in fact doing the best I can for these athletes.

I’m pretty clear on one thing. The wrong approach is to treat the females like males. One of the key tenants of coaching promoted by our own Carnegie Sports Coaching academic group is that what you do, and how you do it is fundamentally influenced by who you are working with(3,4). As women are different from men, the approach to coaching needs to be different too. The challenge is that the differences between men and women are often very subtle, and so the implications of these differences are not always obvious.

To reassure myself that I wasn’t getting things horribly wrong, I started looking for resources that could guide coaches working with female athletes. It was a pretty short search, as these are very few and far between. Incidentally, there are even fewer resources to support coaches working with male athletes. Clearly, more work needs to be done to understand what athletes of different genders need from their coaches. I think that a fundamental problem is that for too long coaches and researchers have simply ignored the differences between male and female sports people. Certainly this is the case in sport science, where female participants are hugely under represented(5). I’ll try to summarize the information that I did find below.

A useful tool to help understand the differences between male and female athletes is the bio-psycho-social model of human development(6). From this perspective, its clear that we understand more about the biological differences between males and females, than we do about the psycho-social differences.

Physiologically, men and woman are not so very different. Once you correct for differences in relative size and muscle mass, men and women display similar strength and endurance capabilities(7). The differences that are apparent are largely mediated by the effects of the predominant sex hormones; testosterone and oestrogen. As a result of the relative influence of these hormones, males tend to have a greater overall muscle mass, while females tend to retain a greater percentage of body fat. In addition, men tend to have longer bones, which creates a mechanical advantage in some sports. The net result of these factors is that in absolute terms, females tend to display about 66% of the strength of a weight matched male counterpart. In highly trained individuals, this difference is smaller, with a difference of approximately 10% in world record performances for males and females in running and swimming.

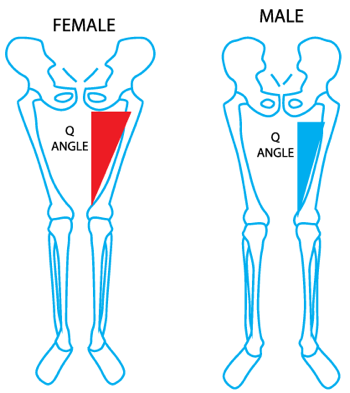

The risk of injury (particularly to the ACL) is higher for female athletes. This is a result of increased joint laxity (one of the effects of oestrogen) and larger Q-angle (figure 2) as a result of broader pelvic bones. This injury risk can be largely mitigated through the incorporation of neuromuscular warm up strategies before training(8).

The least well-publicized difference between male and female athletes is that females are more resilient to fatigue than males. Females fatigue more slowly than males in both running(9) and weight lifting(10) tasks, and recover faster!

Surprisingly, because it would seem like an obvious place to start, there is very little research available on how the menstrual cycle effects female athlete performance(11). Forty percent of exercising women believe that their menstrual cycle impacts their training and performance, but the mechanisms for this effect and how to best mitigate this have yet to be determined.

The psycho-social difference between male and female athletes are far less clear cut, than the physiological differences described above. For a start, while its possible to make broad generalizations about how female athletes think and behave, every individual is different. While some rules of thumb for working with female athletes may be a helpful place to start, every athlete coach relationship needs to be built on its own merits.

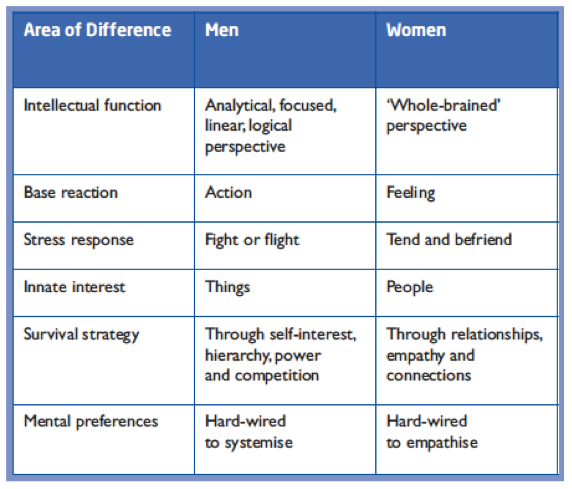

There are some notable physiological differences between male and female brains11. Female brains are more densely packed with neurons, which allow for functions to occur in different brain areas to men, and for neural linkages in brain structure to occur which are not present in men. In addition, female brains are deeply affected by the cyclical variation of hormones in their bodies, meaning that a women’s neurocognitive reality is not as constant as a mans. As a result of these differences, women tend to perceive the world in a slightly differently and react to it in a different way to men. These differences are summarized in table 1.

The differences between male and female athletes described here are a short summary of all the things I’m trying to consider for my coaching. In my following post, I’ll discuss how this information has affected my practice, and hopefully provide some reflection on how effective I’ve been. In the meantime, if anyone has any advice or coaching experience to share with me, I’d be very grateful to hear it.

References

- O’Connor, L. (2017) How the Women’s Rugby League World Cup final can inspire a generation and spur national game. The Guardian 29 November 2017 [Accessed online 31 Jan 2017: https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2017/nov/30/womens-rugby-league-world-cup-final-provides-a-spur-to-form-national-league-and-interest]

- Rowan, K. (2018) Australia Women’s 7s agree deal that ensures pay parity with male counterparts in historic first. The Telegraph 26 January 2018 [Accessed online 31 Jan 2017: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/rugby-sevens/2018/01/26/australia-womens-7s-agree-deal-ensures-pay-parity-male-counterparts/]

- Abraham, A., Saiz, S. L. J., Mckeown, S., Morgan, G., Muir, B., North, J., & Till, K. (2014). Planning your coaching: A focus on youth participant development. In C. Nash (Ed.), Practical Sport Coaching (pp. 16– 53). Abingdon: Routledge.

- Till, K., Muir, B., Abraham, A., Piggott, D. & Tee, J.C. (2018) A Framework for Decision-Making within Strength & Conditioning Coaching. Strength and Conditioning Journal (In press)

- Costello, J.T., Bieuzen, F. and Bleakley, C.M., 2014. Where are all the female participants in Sports and Exercise Medicine research?. European Journal of Sport Science, 14(8), pp.847-851.

- Engel GL (1977) The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science196, pp.129-136.

- Lewis, D.A., Kamon, E. and Hodgson, J.L., 1986. Physiological differences between genders implications for sports conditioning. Sports medicine, 3(5), pp.357-369.

- Herman, K., Barton, C., Malliaras, P. and Morrissey, D., 2012. The effectiveness of neuromuscular warm-up strategies, that require no additional equipment, for preventing lower limb injuries during sports participation: a systematic review. BMC medicine, 10(1), p.75.

- Deaner, R.O., Carter, R.E., Joyner, M.J. and Hunter, S.K., 2015. Men are more likely than women to slow in the marathon. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 47(3), p.607.

- Häkkinen, K., 1993. Neuromuscular fatigue and recovery in male and female athletes during heavy resistance exercise. International journal of sports medicine, 14(02), pp.53-59.

- Bruinvels, G., Burden, R.J., McGregor, A.J., Ackerman, K.E., Dooley, M., Richards, T. and Pedlar, C., 2016. Sport, exercise and the menstrual cycle: where is the research?. British journal of sports medicine, 51(6), pp.487-488.

- Brizendine, L., 2006. The female brain. Broadway Books.

- Cunningham, J. and Roberts, P., 2012. Inside Her Pretty Little Head: A new theory of female motivation and what it means for marketing. Marshall Cavendish International Asia Pte Ltd.