What can coaches learn from video game designers?

We’re losing….. badly!!!

General fitness levels among children are falling off a cliff1. The prevalence of obesity is rising1.

We know the answer is to get children physically active, but we can’t get them to step away from their screens long enough to try.

If you offer most kids a choice between an hour’s sports practice or an hour with their X-box, it’s no contest. X-box every time. Hell, not even an X-box, most children can find something more entertaining than sports practice on their phone.

It’s not even a fair fight. If you’ve ever dared to download a video game , you’ll know that they are inherently enjoyable, and highly addictive. If you compare an average youth sports coaching session to a video game you’ll immediately understand why game designers are at such an advantage. Good coaches will plan before their coaching session, and might spend an hour designing their activities. Game designers invest 1000’s of hours in design and development ensuring that their game is so engaging that it needs to be pried out of players hands with a crowbar.

But what is it about games that makes kids (and adults) so willing to invest hours of concentration in skill development in order to master them? More importantly, what can we learn from video game designers to make our real life coaching activities more attractive2?

1. Performance before competence Did you ever see a child get an new video game and then read the manual before starting to play? No! They just dive straight in and learn by playing. The design of games allows players to start playing before they know how to play, and creates scenarios for them to learn the rules and skills required to move on to higher levels.

How is this different from sports? I often watch coaches spending ages (sometimes more than half the session!) explaining to participants what they are going to do, how they are going to do it, practicing the skills needed to perform the task before actually letting the players do it.

2. Low consequences for failure People often think that losing is a bad thing, that it is a negative experience for a child. Yet children fail/die all the time in video games and they keep coming back for more. In many games the only way to progress is to fail frequently, because each time you do so you learn something new about the game. The point is that failure in video game world has very few consequences, players are provided with multiple lifes and can generally continue from the place where they failed previously.

Compare this to sports where we often spend a whole week preparing for the game, a once off high-stakes opportunity to be successful (or not). If we lose, parents and friends may be watching, and the coach is probably going to spend the next week picking apart what we did wrong and helping us relive it in explicit detail. Children don’t mind losing, they dislike it when there are consequences. Providing multiple opportunities to play without fear of reprisal for failure is a good principle we can adopt from game designers.

3. Pleasantly frustrating Good games quickly get players to a place where they are playing right on the edge of their ability level. The game is challenging, but the goals feel achievable. As a result players fail frequently, but always feel like they were close to succeeding, receive immediate feedback and have multiple opportunities to try again. These conditions create high levels of motivation causing players to stay engaged with the game for hours.

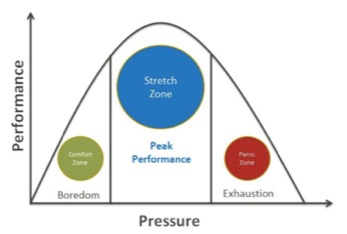

What we can learn from this is to think carefully about the challenge point that we set our coaching activities at. Setting tasks that are too easy will bore our players, setting tasks that are too hard and will quickly frustrate them. Set tasks at the right challenge point and player will stay engaged for hours (Figure 1)!

The relationship between performance and pressure. Players learn fastest and engage most when stress levels are optimal.

4. Agency Games give players choices, allowing them a level of control within the gaming environment. This can be aspects as trivial choosing what your avatar wears, or bigger decisions like what route to follow or tactics to adopt. Within the game environment, players are autonomous. They can go where they want to go and do what they want to do, they are free to explore.

Sports practices are generally exercises in having your time organised for you. The coach has agency and tells players what they are going to do and when they are going to do it. When is the last time you asked your players what they want to work on during practice?

5. Well-ordered problems Most games work on the principle of ‘cycles of expertise’. The first step in this cycle is the introduction of a new problem, which requires the learning of a new skill to solve it. Initially this is challenging, but with a little practice the player becomes competent and starts to overcome the problem easily – this develops confidence3. Once the skills are mastered, players are challenged to develop new skills or to combine different skills to solve new problems. This is the whole point of levels, each level exposes the players to new challenges and allows them to get good at solving them2.

Sports are chaotic – there are a lot of things going on at once, and learning to play well can be overwhelming and frustrating at the same time. You can help your players by providing clear objectives linked to their skill level so that the can feel like they are becoming more competent. Objectives shouldn’t be about winning or losing, they should be about executing skills or tactics. Remember kids lose at video games all the time, but keep coming back because they can sense themselves getting better.

6. Information Just in Time or On Demand Games don’t tell you everything you could ever possibly need to know at the start. They let you play until you come up against a problem you are unfamiliar with, and then provide you with hints, or allow you to ask for tips. Or they allow you access to new skills or ‘powers’ only when you need them. This way when you learn something new about the game you are excited about it and are given the opportunity to apply that information immediately.

Humans are really bad at learning things out of context. We need practical experience to make new information meaningful. Next time you want to teach a new tactic or skill, why not use the whole-part-whole approach? Start your practice with a game or activity that presents players with a particular problem and allow players to struggle with it for a while. Once they are suitably frustrated, stop the activity and provide the technical or tactical advice needed to solve the problem. Allow some time to practice the skill or tactic. Once they have acquired the what they need to be successful, put them back into the original activity. Stand back and admire the happiness and sense of accomplishment.

As I said at the start, video games didn’t become addictive by accident. A lot of very clever people, have thought very long and hard about how to create experiences that keep players coming back for more. But this knowledge isn’t exculsive to game designers. Hopefully, this article will have provided some ideas about how you can ‘gamify’ your sports practices. Spending some time thinking about what makes activities engaging and enjoyable can turn your coaching around. You know the old saying…if you can’t beat them, join them! Let’s fight fire with fire!

References

Tremblay MS, Barnes JD, González SA, Katzmarzyk PT, Onywera VO, Reilly JJ, Tomkinson GR, and Team GMR. Global Matrix 2.0: report card grades on the physical activity of children and youth comparing 38 countries. Journal of physical activity and health 13: S343-S366, 2016.

Gee, J.P., Learning by design: Good video games as learning machines. E-learning and Digital Media, 2:5-16, 2005

Bandura, A. and Schunk, D.H. Cultivating competence, self-efficacy, and intrinsic interest through proximal self-motivation. Journal of personality and social psychology, 41:586, 1981